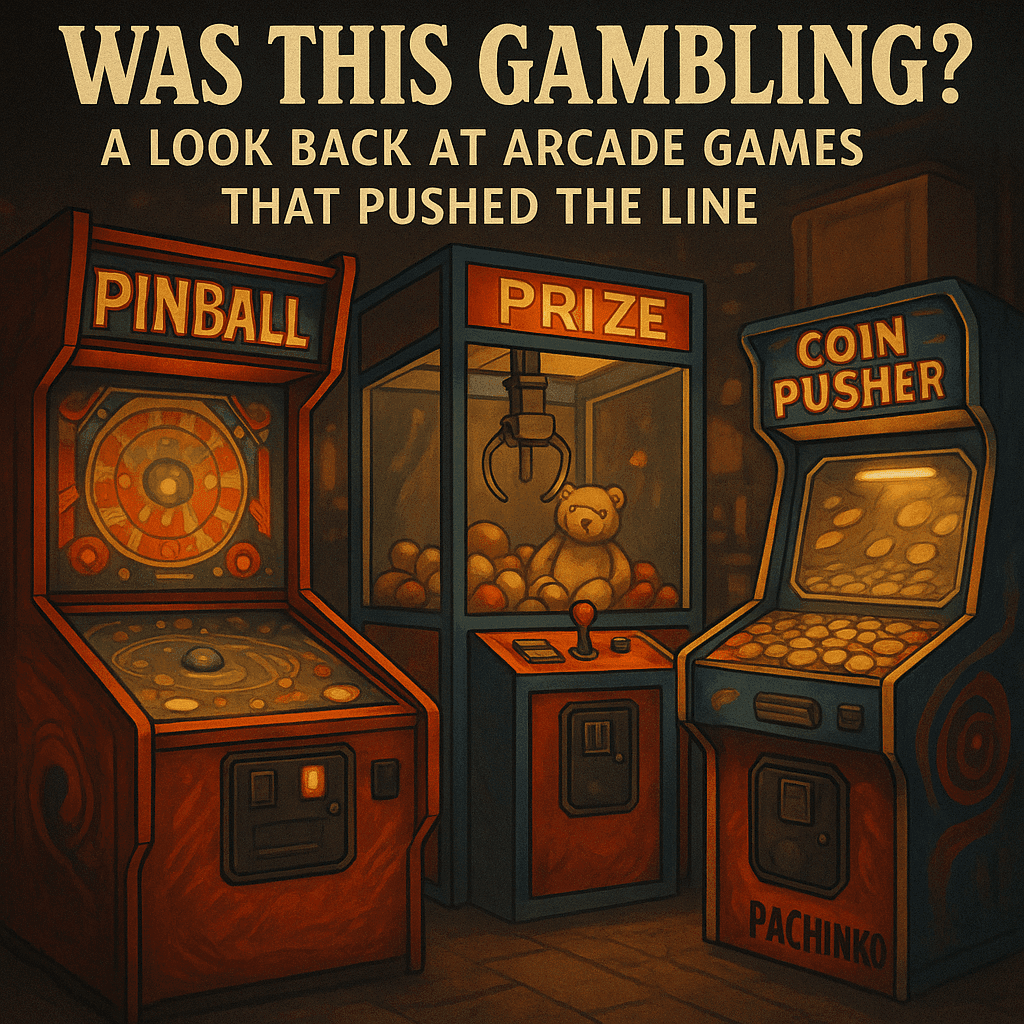

Was This Gambling? A Look Back at Arcade Games That Pushed the Line

4/8/2025

In the mid-20th century, arcades seemed light-years away from what we now think of as gambling. But the distinction between arcade entertainment and betting was fuzzier than you might imagine.

This is the thing: certain early arcade games didn't merely accept your coin in return for a good time, they teased at paying you back in kind, sparking legal and ethical issues that lasted for decades.

Actually, before online casino experiences became popular, arcades were struggling with games that looked awfully similar to payout machines in casinos. But did they really push the line?

To decide whether arcade play crossed into gambling, we need to assess each game by its mechanics, its payouts, and how laws treated it. Let’s go.

- Pinball: Forbidden as gambling, rescued as skill

Pinball in the 1930s had no flippers and was strictly based on chance. New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, and Washington, D.C., prohibited the machines during the early 1940s as gambling machines associated with organized crime. New York prohibited the machines starting January 21, 1942; police confiscated more than 2,000 machines, disposing of most of them in public raids coordinated by Mayor La Guardia.

The tide turned in 1947 with the introduction of the first flipper-featured pinball machines, such as Humpty Dumpty, which provided players with actual control. Roger Sharpe, in 1976, showed pinball's skill factor to the NYC Council, correctly calling his shot, and contributed to rescinding the ban. Pinball bans across America disintegrated: Los Angeles overturned its ban in 1974, Chicago in 1977, and so on.

- Payazzo and Pachinko: Mechanisms built on gambling

In Finland, Payazzo, or Pajatso, appeared in the 1920s. Flicking coins at slots was played by the participants; hits brought several coins back as rewards. That's pure betting by today's definition. While payouts wouldn't always be made in money, the win-or-lose mechanism clearly reflected gambling.

Similarly, in Japan, pachinko is a ubiquitous gambling arcade institution. You shoot steel balls into a machine; prizes can be traded indirectly for cash through tokens. That legal hole in the wall makes pachinko available everywhere and nearer to slots than bumper cars.

- Coin Pushers & Claw Games: Kids' play, adults' stakes

These devices look harmless: insert a coin, and pray for a prize. But they are based extensively on near-miss formulations, rigged payout cycles, and reward schedules in the style of slot machines. Many variations pay out in coins or tokens. US and UK research indicates that early exposure to these games is linked to increased risk of gambling later in life: coin-pusher players were 3.5× more likely to have developed gambling problems.

Coin pushers are illegal in most US states if they provide prize values. Even the ones in arcades without value payouts are in a slim legality. A South Dakota legal opinion identified quarter-pushers as illegal gambling machines because results are based on chance and not skill, even though the player glides the coin themselves.

- Redemption/Ticket Games & Luxury Arcades: Prize play with casino logic

Wheel‑themed redemption games, imports of the early 1990s such as Wheel 'M In, and contemporary ticket games commonly exchange coins for tickets or wrapped prizes. Tickets are not often redeemed for cash, but the graphics reflect gambling loops: large rewards, near misses, increasing bets.

Still more dramatic are high‑end arcades (e.g., upscale locations in Vegas or NYC) that charge $10–20 a play on designer product‑laden claw machines such as Hermès or computers. These machines are engineered to pay out seldom. They appear to be amusement devices but operate as micro‑casinos with real monetary risk and programmed odds.

Most jurisdictions geo‑legalize them only when prize values remain below thresholds. Otherwise, they can be prohibited or legalized as gambling machines.

- Medal games: Japanese arcades flirting with casino zones

Japan developed a category of medal games that hangs in a balance between arcade and gaming. The players buy medals using money and play roulette‑like, horse‑racing video games, or slot‑like medal games. Although tokens cannot be redeemed for money by law, the experience resembles betting more than skee‑ball.

These games, even if solely ticket-based, take big cues from slot and table‑game design, and they entice players through that combination of illusion of skill and randomness.

- Arcade-to-Casino Conversions: Games into bets

Konami remapped Silent Scope and Beatmania as hybrid pachi-slot machines that returned cash or medal rewards. These adopted known branding but incorporated actual gambling mechanics, transforming arcade machines into regulated output devices. Because they paid out, they were considered gambling equipment, not amusement models.

How Did the Law React to Such Arcade Games?

- Pinball: Bans started in the early 1940s: New York (1942–1976), Chicago up to 1977, Los Angeles in 1974. Winnipeg broke skepticism when Roger Sharpe demonstrated that pinball was based on skill. The NYC Council unanimously removed the ban, paving the way for gradual adoption across the country. A few local bans exist on the books (e.g., in South Carolina, minors, or Kokomo, Indiana), but enforcement is uncommon.

- Coin Pushers & Prize Games: South Dakota made quarter-pushers illegal. In statute, they are slot machines because they pay out value based on chance. LegalFix states the majority of US states have banned coin pushers; where permitted in the states, there are strict regulations limiting prize value and requiring licenses.

- Payazzo & Pachinko: Generally regulated as gambling machines: Payazzo was integrated into Finland's state-run betting system; in Japan, pachinko is regulated under strict conditions even as arcade-type establishments abound.

- Hybrid Arcade Gambling: Machines that offer cash or token payouts fall under gambling regulation regardless of branding, a critical boundary for machines like pachi-slot conversions and redemption arcades.

Conclusion

Arcades have repeatedly crossed into gambling territory, sometimes by design, sometimes by accident. The evolution of flippers, medals, and claw machines shows a trajectory from innocent fun to structured risk-taking.

When it all came down to it, arcade design and law repeatedly disagreed on a single issue: does randomness prevail over skill? Where randomness held sway, the law intervened.

Arcade history discloses a single fundamental truth: human play is susceptible to the temptation of risk, and in large part, game design exploited that desire. What was originally a nickel for entertainment occasionally became a bet in disguise.

Did you enjoy any of these arcade games growing up? What is your opinion on these games pushing the line? Share your thoughts.